When April Comes

Robbie Simpson is a world-class mountain runner from Scotland. Having developed his skills on the trails he’s turning his attention to the road, and looking to Rio.

Words and Photos by Emmie Collinge and Phil Gale

Hunched ungracefully over plates of food, we focus on refuelling. The Austrian restaurant in which we’re sitting is full of elderly locals, enjoying their Saturday afternoon, wholly disinterested in us or the relevance of our somewhat mechanical refuelling process. We’re recovering from this morning’s marathon, and sharing lunch and conversation with Robbie Simpson, a 23-year-old world-class mountain runner from Scotland. He’s just been through what would be a career-defining year for most people, but it’s not enough for him — now he wants to turn his hand to running’s toughest, most competitive road event: the marathon.

The distance is one Simpson knows well — he reached the summit of this mountain marathon in first place only an hour earlier — so how different can a road marathon be? And does he know what’s letting himself in for? Unlike the gruelling progress of a mountain marathon, Simpson has set himself the toughest of goals: selection for the Olympics.

Mountain running is often seen as a quirky side act in the arena of running, the black sheep-like relation to the roads. But as we sit in this Tyrolean restaurant mid-way through the three-day Tour de Tirol off-road running race, all of our legs — and stomachs — are feeling the strain. It’s a strain that’s remarkably similar to the experience of completing the same distance on the road. After meticulously outlining just exactly how much we should refuel in the restaurant before the following day’s off-road 23 km race, Simpson, explains how he’s all too frequently seen as a guy who runs up and down hills: “There are a lot of great runners in Scotland, but I’m still brushed off as just a ‘hill runner’. Running a road marathon will show them that I’m actually an athlete, not just a guy who can run up and down hills where there’s no competition.”

With the Tour de Tirol marking the end of Simpson’s season, one that saw him finish third at Serra Zinal — one of the unofficial Diamond League standard competitions in mountain running — and take the bronze medal at the World Mountain Running Championships, you could almost wonder why he wants to make the change. “I’m coming out of my best mountain season to date and I know I could run a 2.18 or a 2.20 marathon right now if I needed to, but what would be the point in that?” As he methodically chews his chicken pasta he continues: “Next year is an Olympic year; the time of 2.14 is there and it’s the only real target you could set yourself.” For Simpson, the Rio qualifying time is what’s driving him. And although he’s highly aware of the stiff competition when it comes to selection, he’s going to follow his training schedule resolutely. After all, he has never been one to conform to the norm or shy away from a challenge.

Currently a full time runner, Simpson has chosen to base himself in Southern Germany at the epicentre of the European mountain running scene. A Countryside Management graduate he explains how the act of pursuing a career in athletics is perceived differently outside of the UK, jokingly declaring that he’d have long been kicked out of his parents’ house for not working immediately upon graduating from university. “At the moment I have the luxury of time on my side and I can tell from the past season that I’m fitter than I’ve ever been. Who knows what commitments and work I might have in four years time? Now it’s possible for me to give 100% in terms of training and commitment, so why not?”

After a fairly standard introduction to local athletics and middle distance track racing, Simpson’s running career took an unconventional trajectory. Growing up in the rural town of Finzean in the Highlands of Scotland, Simpson always had an affinity with mountains, fishing and spending time in the outdoors. After joining the local athletics club aged of 12, his natural endurance led to a few early victories in track races, but as he himself says, every track looks the same: it was the Scottish hills that really sparked his imagination. The serendipity of Simpson’s childhood was that he actually grew up at the foot of Craig Choinnich, the Scottish mountain that claims to have hosted the first ever mountain race, when in 1050 AD King Malcolm III set about finding the fastest runners to become his royal messengers. There was no job interview, just an uphill race between the hopefuls to the top of this very mountain. Perhaps it was this very heritage that prompted Simpson’s move from the track to the mountains — helped by the coincidence of 14-year-old Simpson winning a book that documented this ancient race. He certainly wasn’t unfamiliar with the act of running in the mountains though, and his favourite pastime still involves taking his fishing rod and heading into the hills. This simple act of running from loch to loch rings true to his Scottish roots and goes hand-in-hand with his introduction to the sport in which he would later become one of the world’s best.

He first represented his country in European mountain races aged 15, seeing more of Europe each summer and recognising his potential on the tougher races. These early successes gave him the impetus to forget the dream of running at the Olympics, and instead, after graduating, relocate to Europe, emulating the greatest mountain runners who opt for Alpine altitude over Kenyan plains.

Simpson is pragmatic in his aspirations and attitudes. His modesty means he is the first to admit that he may not be the fastest over the 26.2, but he does see great advantages that will be gained from the upcoming marathon training: “My running and technical ability are already fairly equal, unlike other competitors who may be stronger at one aspect of mountain running. I am certain that the training for the marathon in April will help my speed on the trails, but it could have a detrimental effect on my climbing.” He pauses for a moment as he collects his thoughts: “I mean, perhaps mountain runners are not necessarily as fit as road runners, but I am definitely strong on the roads too, and I have already run a 30 minute dead 10 km. This build-up for April and the target time will hopefully give me an advantage when I come back to mountain running.”

As we wait for the bill from the now harassed-looking waitress,, the stream of runners coming down from the marathon’s mountaintop finish increases. This has been a hard day for all, but as with any stage race, those who finish first get more time to recover, winning the race to the table if you will. Simpson continues with inspiring optimism as he reels off the training plan that’s about to start: “It’s not going to be like a mountain race,” he says with a smile, “but once I’m used to the distance and the speed, then it should be ok.”

Under the guidance of his Austria-based British coach Martin Cox, Simpson’s (potentially fleeting) diversion to the roads as an aspirational Olympian will follow a strict periodised training schedule in the run-up to April. Cox, himself an elite mountain and successful amateur road runner, is currently applying his expertise to create blocks of training, which Robbie then dutifully follows on his own in Germany. Inspired by the Canova school of thought on marathon training, our eyes water at the rough outline of the programme that Simpson reels off: “Basically the theory is to train yourself to run at your desired pace efficiently, so I’ll be doing race-pace for certain distances before building up 20km, then 30 km etc. First I’ll get as fast as possible early on until I’m comfy at the target pace. And it is only once my body recognises the pace,that I’ll increase the length of the long runs at the target pace.” He surmises that learning to ‘hang on’ seems logical, and that too frequently runners add in the speedwork too late in the day, effectively ‘losing’ their endurance before the marathon arrives. “Basically marathon running is about getting your head around the pace and controlling your effort. If you can’t do 20km at race-pace then you’ll have to reconsider your target time,” he says with a shrug.

Yet with the kilometre splits to reach 2:14, and even 2:12, already etched into his mind, Simpson’s programme will involve focusing on doing his longer runs during competition. A staunch competitor who always races to win, he sees it as a way to get more out of the training: “If you’re smashing yourself over 35km, why not get something out of it?”

Over the past decade Simpson has dramatically reshaped the mountain running landscape in the United Kingdom. Consistently proving himself to be among the world’s elite, Simpson retains a refreshing down-to-earth nature, neither playing the fame game, uploading epic scenery shots from every run or preaching about his numerous victories. These are humble Scottish traits, and leaving the restaurant to head to hotels it is clear that this young talent is very well-liked, as the locals wave out of car windows complimenting him on today’s victory. He smiles bashfully.

Next weekend, he tells us he’s flying back to Scotland for the Scottish Athletics Awards Ceremony, where he’s up against Laura Muir (fifth in the World 1500m final and winner of the Oslo Diamond League), Lynsey Sharp (who ran 1.57.71 to break the Scottish record) and Ellidh Child (bronze medal winning team run at the World Championships in the 4x400m and 6th in the 400mH). Typically modest, Robbie waves away any comparisons with these track athletes, downplaying his success in his chosen discipline of mountain running. Yet when the conversation returns to the marathon, he is resolute, seeing the accomplishment of the Rio qualifying time as his chance to be the exception and prove that mountain runners are exceptional athletes in their own right.

Isaac Kiprop, Fred Musobo and Petro Mamu are arguably the three best mountain runners and they’re all of African origin. But while they’ve all clocked times that are highly respectable on an international stage (think 13 minutes, 28 minutes, 62 minutes and the like), they have not quite been able to turn their dominance in the mountains into performances on the roads. Yet one could argue that they have never fully focused on these events, seeing their opportunity for money and success in the mountains. Simpson himself cites New Zealand’s Jonathan Wyatt and England’s Billy Burns as discipline-flaunting role models, both of whom reached dizzy heights in mountain running and clocked rapid road times, with Wyatt still holding several national NZ road records.

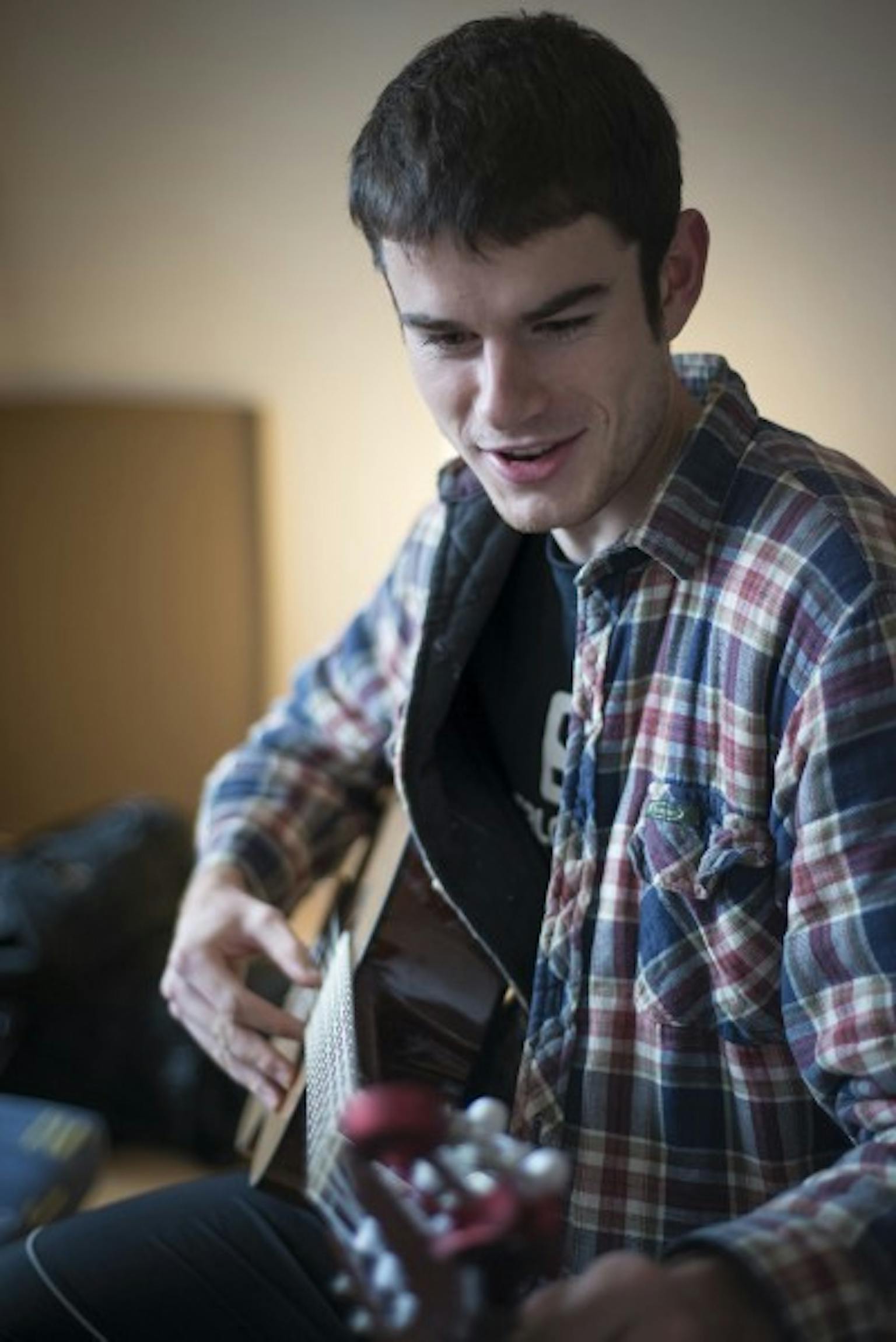

Simpson’s realism and direct manner continues as he planks down on a foam roller back at the hotel. “Realistically I will never be good enough to make a living out of marathon running, you’d have to consistently run at least 2:10. If I don’t make Rio, then my next target will be the Commonwealth Games. But we will see, as with all my running, the less time I spend thinking the better it goes. That is what my fishing rod and guitar are for.”

Is it the draw of fishing that keeps Simpson coming back to the mountains or just his method of switching off? It is more than merely urban legend that Simpson travels with his fishing rod to major races, he continues: “I had my telescopic fishing rod with me when I went to this year’s World Championships in Wales. I tend to always have it with me, it packs down really well. In Wales I did not need it though, because the team were great to be around, but I do remember a race in Norway where I spent most of the downtime fishing in rivers and lakes, then cooking what I’d caught in the evenings. It’s all to keep my head clear.”

To date though, Simpson has only raced two marathons — both off-road, including Switzerland’s renowned Jungfrau with its mountain top finish (3:08) and this morning’s Tour de Tirol, where he clocked 3:09 to cover the 2,400 metres of climbing. “I hope this marathon training will improve my mountain running. It’ll keep my fitness going and gives me a great target. All those kilometres will improve my speed and endurance too. I won’t be doing all the intervals on the road either, I’ve got some great mellow trail loops around my home where I can still run properly. I might lose some uphill strength, however, but being a bit lighter may be beneficial. I am around 70 kg while many of the top mountain runners are usually 60 kg.”

On paper he might not appear the strongest contender, but after seeing the grit and determination with which the 23-year-old approaches mountain running, his aptitude for enduring long distances is undeniable. And his belief in the training schedule that Cox has designed for him is heartening. As marathons are mightily unpredictable, with so many burning out before just mere kilometres before the finish line, it’s very refreshing to see that confidence that Simpson exudes in comparison to many pre-marathoners, level-headedly arguing that there’s nothing stopping you (bar a head wind, for example). “It’s just a case of getting the legs used to the distance and the speed. If I can survive the training then the race will be doable. And at least I have an aim, there is no point doing things by half measures.”

For more interviews like this, check out Meter magazine from Tracksmith. Issue #03 is on sale now and features athlete profiles, race coverage, history and cultural insights to running around the world.