Uncle

Malachi

Psychoblackology, Multipotentiality, and Rejecting Limits

Words by Reyeoul Lakeshore

If memory serves me correctly, my uncle Malachi’s legendary existence entered my consciousness as I perspired post-run on a Californian summer morning.

I approach the industrial-style gate that stands guard between my mailbox and the sidewalk. The July sun is searing the metal, causing it to expand and swell; after a few nudges and a solid kick, I manage to swing it wide, stepping through the gateway towards the mailbox. On any other day, I would be too tired and too preoccupied post-run to bother with the mail, but today, the little black box is needling my subconscious.

My legs still unsteady, and the sweat drying rapidly in white circles, I tear open a mundane envelope.

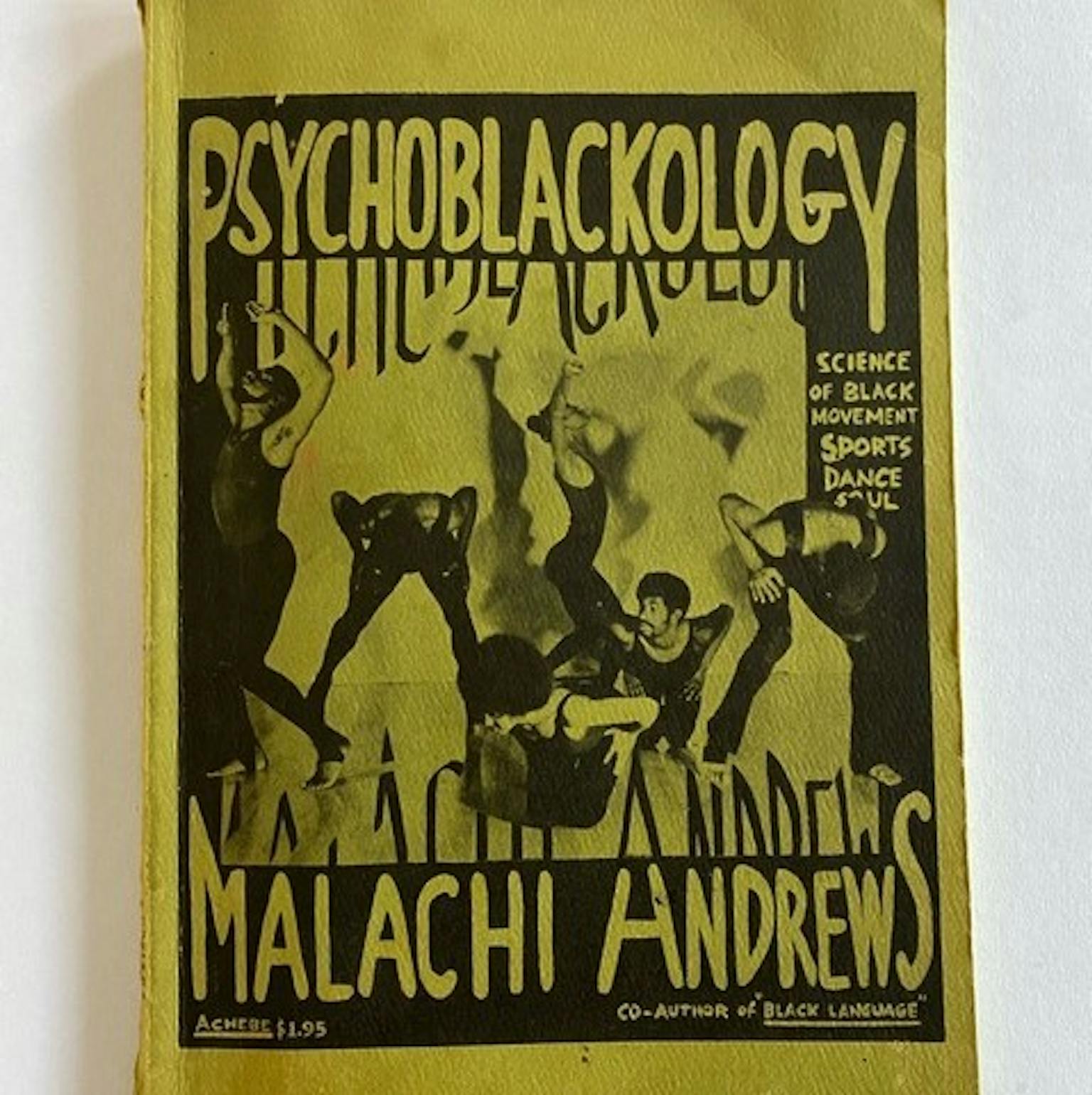

A book. Psychoblackology: Science of Black Movement, Sports, Dance, Soul. An exploration of physical education, dance, drama, play, gymnastics, recreation, and soul experience.

Without hesitation, I begin a deep dive into this zine-style, 70s jive talk, Afro-centric artwork. A guide with the intentions of un-teaching the suppressive ideologies of the 1970s, as advanced by athletic institutions at both professional and amateur levels. An exchange of dominant ideology for Black science, incorporating language, nutrition, movement, and spirit to elevate the Black athletic experience. I am sure that Uncle Malachi’s intention was to open the portal for Black folk to become powerful multipotentialites, as he so powerfully demonstrated through his own extraordinary life. Malachi was a Black man and a polymath: an athlete, a gymnast, an artist, a coach, an educator, a kinesiologist.

In his words, Malachi was a human scientist, probing the human spirit, connecting the mind and the body through kinesthesia.

Unconscious to the reality of those proficient in multipotentiality, both in my youth and in young adulthood, I concealed my curiosity. I became a chameleon among my diverse peer-group. My consciousness became one-dimensional as I appealed to the interests of the group at hand. My subconscious was fleeting between the artist, the athlete, the musician, the showman, the shy man, and the teacher. I struggled to accept myself holistically.

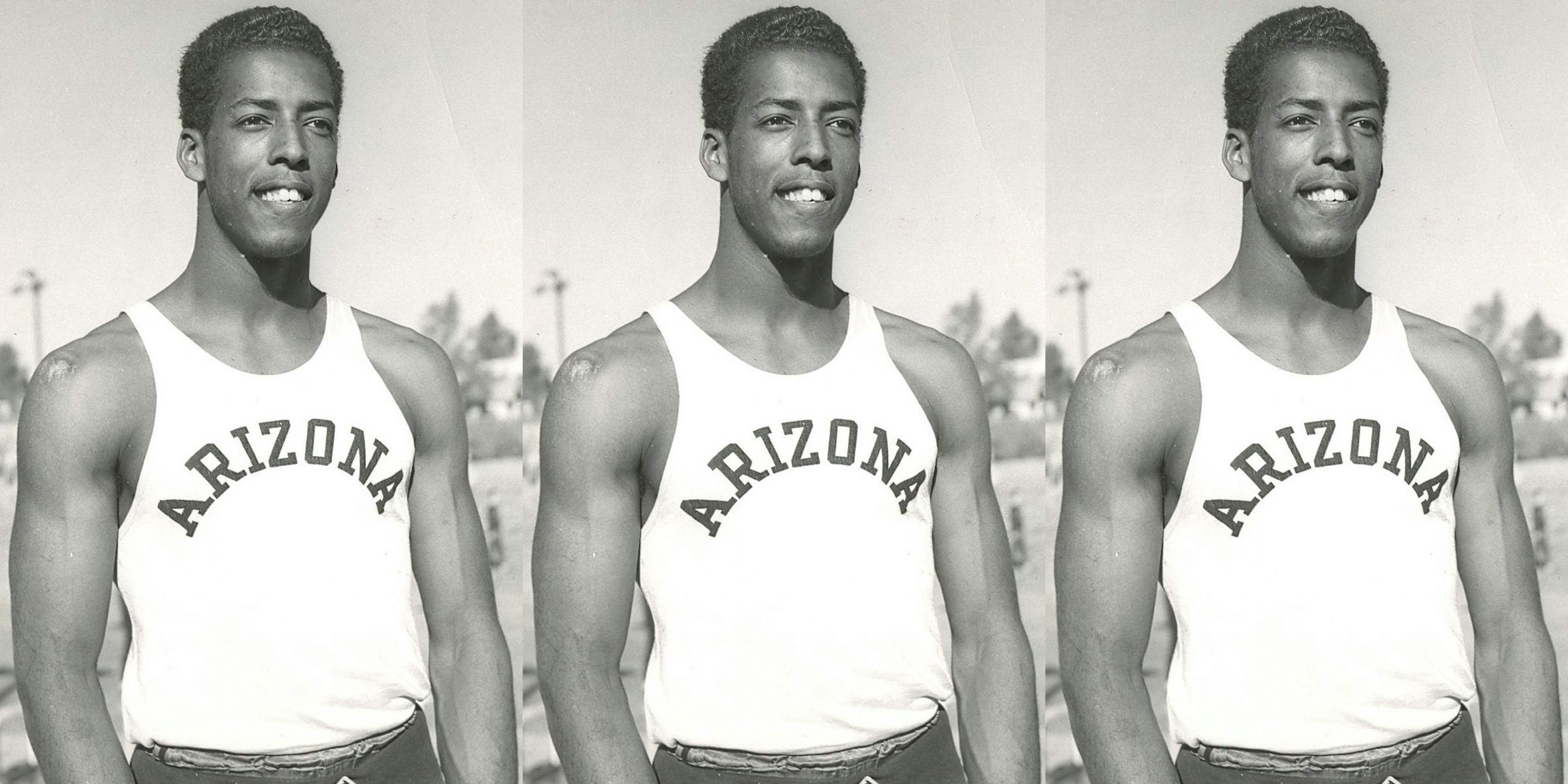

Born in 1930’s Los Angeles and growing up east of the 110, Malachi cultivated the ability to transcend the limitations one might imagine exist for a young Black boy. One of five siblings, he showed an early preference for art and movement but he was a child of the silent generation, a generation that would grow into leaders of the civil rights movement. Many an afternoon was spent leaping between his family home and the humble church, erected on the same property by my great grandfather, Mays Andrews. Movement fine-tuned a talent he would later use to his advantage as he entered into collegiate athletics. Malachi grew up in Los Angeles, and through an emboldened vision of empowerment and steadfast talent, he outran his socialized destiny and predetermined potential.

As an athlete, Malachi was no underachiever. He participated in state and national competitions, created new records, and was even named as an alternate on the 1956 United States Olympic Team in Long Jump’s chosen sport. He was the First Arizona trackman to be named to a U.S. international team, competing in the Caribbean in 1956. Malachi never let his athletic profile overshadow his achievements in other aspects of his life. His athletic prowess did not box him in.

I could scrutinize, dig up, and unearth old diaries, examine him under a microscope, try and find the bad and the ugly of his life from cousins and family members. But why? Malachi left room for exploration through his writings

My personal zeal for running with holistic intent, encompassing my appetite for arts and expression through movement, has become a lifelong exercise, an ongoing curation. The discovery of Malachi feels accidental. It came at a time where I was eager to seek out others belonging to the same tribe of non-monolith athletes, and I was granted the knowledge of a man in my direct bloodline.

When the long jumper takes flight, defying gravity as they run through the air, their destiny is inferred by the impression laid in the sand by his or her body, the physical fallout creating a line in the fine gravel of the landing pit. This line becomes the barrier to which the athlete must subsequently leap over. The long-jump is an elegant performance that takes skill and determination. The repetitive nature of the athlete prevailing over the line is the embodiment of the barriers that Malachi Andrews leapt over in his own life, both as a multipotentialite and as a Black man.

Malachi was an unapologetic Black advocate. He believed a racist structure within the physical education and sports systems of America simultaneously hindered Black athletes’ performance while attempting to benefit white athletes. Malachi argued that the very same methods were detrimental to all athletes, as the structures lacked a shared language of movement. The creation of a superiority complex across color lines denied the white athlete the ability to learn from the Black experience. A white athlete can have the “superego” to believe that their abilities are superior to those of their competitors on the starting line. But when that belief is founded purely on pigmentation and not their accolades, the athlete can lack the self-awareness one needs to improve oneself. Not running with soul, but running on institutionalized privilege, distant from “individuality and soul.”

In contrast, the Black athlete is only seen as athletically powerful as they become “mean and violent with hate” as a result of the struggle they endure as a Black person. Many Black athletes fall victim to this thought process, suppressing the emotions and passion evoked by athleticism to avoid these labels. It is not until the Black athlete can tap into the humanity of movement that they can rise above this stereotype, developing the freedom to move beyond the scientific theory that dominates institutional athletics and tap into the “soul experience.” While science has its value, there is much that can never be explained through scientific theory. Malachi believed that all athletes can benefit from expanding their minds beyond dogmatic prescriptions.

While researching uncle Malachi, his passion for advocacy became evident when I discovered a New York Times article from the 1972 Eugene Oregon Olympic Trials on the Hayward Field. One of Coach Malachi’s athletes, Willie Eashman, a Black man representing what is now known as Cal State East Bay, had been duped by the readmission of a previously disqualified white runner. Malachi had coached Eashman, intending for him to be the first Black American to break four minutes in the mile. The readmission of the disqualified runner led to Eashman's unfair elimination in the semi-final, placing fourth in 3:45.9, vs 3:45.1 for the previously disqualified runner in third. As per the article, Malachi cried out, “somethings definitely wrong… We’ve got to look into this situation right now.” He was determined that his fellow athletes deserved recognition and argued that the situation was “racist-oriented.” Remnants of segregation stubbornly showed their face as the white athletes went about their business, and Malachi “consulting with a group of blacks” assembled in the corner. Amongst those congregating were Lee Evans, Olympian and prominent leader in the intersection of sports and political activism, and John Smith, a 1971 Pan American Games 400M winner. Although we are not privy to the discussion that ensued, their activism against the injustice was enough to readmit Eashman to the finals. He went on to run the 1500M the next evening, regaining the opportunity to try that was rightfully his to begin with if ultimately missing his chance at the Olympics.

Sports-led activism is nothing new. But contemporary white allyship at the intersection of sport and social/racial justice has proven to be an essential ingredient in the antidote to toxic, racist institutions. So often, we focus on the science behind the athlete and that we miss the collectivity of the human condition. Opening the mind beyond the scientific theory permits the Black athlete to express themselves in all facets, stoking racial issues “awakening into white allies” consciousness. The old accolade of “shut up and dribble” turns into “we hear you.”

In Phsychoblackology, Malachi says, “we see clearly our new path through all the maze of tradition, convention, and dogma of sports in society. Our efforts are part of the people's struggle to mature a soul relationship between all men and women in sports and physical expression as an art.” I was always aware of the bigger picture, whatever the sport I participated in, but I wasn’t privy to the collision of sport as an expression of art and movement. I was playing tug of war between my soul and what my coaches asked of me, limiting my movement and expression to fall in line with my teammates. I conformed to their idea of an athlete: the jock with limited substance and idealism. I did not utilize the exploration of mindfulness and expression as a tool towards a holistic athlete; instead, I became dissatisfied with sport as an outlet, and ignoring its potential, I turned to the arts, quitting organized sports altogether. In hindsight, my focus on music wasn’t the answer as I struggled to fly through my senior year with one wing clipped.

My awakening to uncle Malachi was serendipitous – like hearing a song by your favorite artist you never knew existed. I accept that I am a runner, but what others may define as a runner is not how I would define myself. I carry with me a smorgasbord of interests, and after years of containing them in separate spaces for fear of losing them or losing myself, my bag is spilling over. My interests are learning to meld. Through my discovery of Malachi Andrews, I am discovering that my multiplicity of interests is not an anomaly. With this knowledge, I know that I could never again limit myself to existing solely as “the runner.”

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of METER magazine.