Comrades

The Race That Shaped a Nation

Words by Menzi Ndhlovu

It was a pleasant June morning in 2018 when Olwethu Makwati, Nontobeko Andlovu, David Viera and Kayla Miller lined up outside Pietermaritzburg City Hall.

Alongside them near the imposing Victorian structure on Chief Albert Luthuli Street were 25,000 runners, all from different walks of life, but all waiting to tackle the world’s oldest and most populous ultramarathon – the Comrades Marathon.

As a physical undertaking, the Comrades is arduous.

Each year the race alternates between a shorter and relatively steeper “up” run starting in Durban and finishing in Pietermaritzburg, and a slightly longer, flatter “down” run, starting in Pietermaritzburg and finishing in Durban. Both routes are typically in excess of 87 kilometers, or nearly 55 miles, taking runners along the country’s hilly eastern escarpment in KwaZulu-Natal province. This includes the infamous “big five” hills which primarily account for the 1,000m elevation gain in both the up and down runs.

Testament to its difficulty is the race’s attrition rate. On average, more than 20% of runners fail to complete the race each year, a rate that holds despite the seemingly generous cut-off time of 12 hours and a relatively rigorous qualification process that “selects” for seasoned runners. In order to qualify, runners must be over the age of 20 and have completed a full marathon in under four hours and 50 minutes. Within the race itself, there are also five cut-off points that runners must reach by a designated time.

More remarkable than the physical spectacle is the history of the race, whose checkered nature closely mirrors that of South Africa, and whose meaning has evolved in tandem with South Africa’s transition to a non-racial and non-sexist society.

The first installation of the Comrades Marathon was run on May 24th, 1921 – which at the time was (British) Empire Day – with a field of 34 runners. The race was the brainchild of Word War I veteran, Vic Clapham, who had participated in the lesser - Known East Africa campaign of the Great War. This saw Clapham and thousands of other conscripts from the former British-ruled Union of South Africa march nearly 2,700 through treacherous terrain in the former German East Africa.

In commemoration of this and to celebrate “mankind’s spirit over adversity,” Clapham founded the Marathon, which he intended to be a “unique test of the physical endurance” of participants.

His objective of pushing runners to the limit was easily met in South Africa’s varied terrain. But crucially, there was little by way of a genuine and inclusive sense of camaraderie.

Politically, the Comrades Marathon of the 1920s was a product of its time: a racist and sexist South Africa in which people of color and women were disenfranchised and prohibited by law from participating in formal sporting activities. This was reflected in its entrance requirements: participants had to be white and male.

Accordingly, the diverse line-up we met in Piemaritzberg in 2018, including Olwethu (a Black man from a township in Cape Town), Nontobeko (a Black woman from a township in Johannesburg), David (a white man from a suburb in Johannesburg) and Kayla (a mixed-race woman from a suburb in Johannesburg) was unimaginable for much of the race’s history – for 54 years to be precise, until the race was opened up to official participation by women and people of color in 1975.

Ironically, during this period the Comrades Marathon was not looked upon with disdain by the plethora of non-white and female athletes who were excluded from participating. According to Dingane “Ace” Kweyama, a 64-year old distance runner from Soweto who has participated in the Comrades on five occasions, the exclusively white Comrades was viewed by the Black community as a sporting spectacle like the Olympics prior to 1936.

“While Black runners felt hard done by due to the exclusion, they knew that whites were intimidated by the competition that would be posed by Blacks,” says Dingane. “They know that when we go, we go.” Dingane goes on to cite Jesse Owens and the evolution of American and global sports following the inclusion of Black athletes: “While it was the preserve of whites, it was only a matter of time that Blacks would participate; like apartheid, all this nonsense would come to an end.”

Indeed, for the older non-white population like Dingane which lived through the apartheid era and the exclusionary period of the Comrades, the desire to participate in the race was not only about testing oneself physically, it was an act of protest and a bid to correct the prevalent notion that Black athletes were inferior and incapable. This came at a time when segregationist policies and apartheid – which promulgated the narrative of Black inferiority – was facing mounting opposition from liberation movements.

For women of color, the struggle was manifold, according to Tlale Mokgosi, a 60-year-old Black woman from Soweto who has also participated in two editions of the race.

“Not only were we fighting against exclusion based on our race but also against our gender,” she says. “We wanted to run the comrades because we wanted to prove to white people that we, as Black women, were capable. We also wanted to crush some of the gender stereotypes inherent in our culture, like the fact that we were only good enough for chores. Winnie Mandela and others were doing it in politics, we thought, why couldn’t we do it in running?”

But such acts of protest which paved the way for the diverse quartet of Olwethu Makwati, Nontobeko Ndlovu, David Viera and Kayla Miller began much earlier than commonly thought.

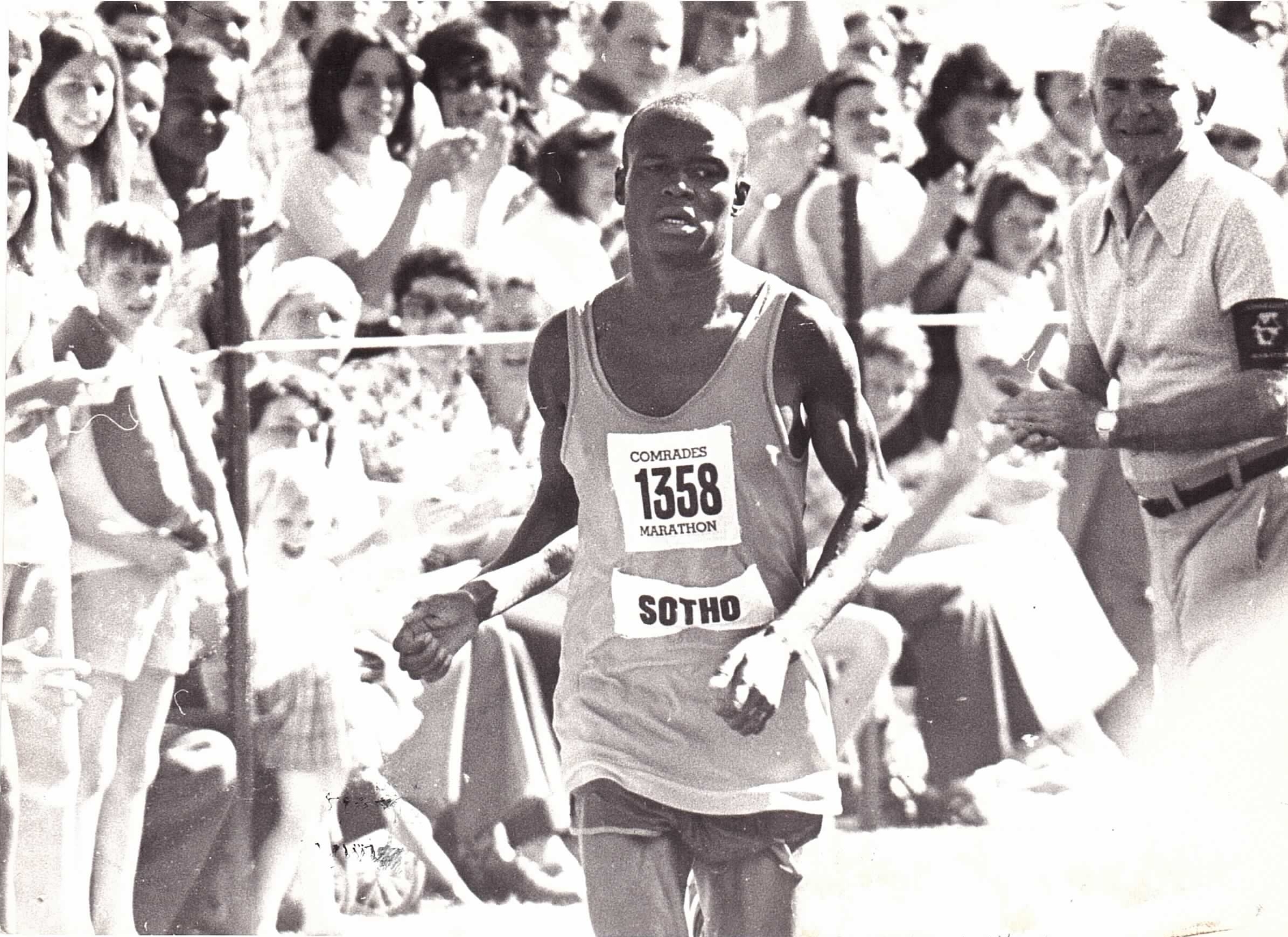

As far back as 1935, Robert Mtshali became the first Black runner to unofficially complete the marathon at an estimated time of nine hours and 30 minutes. Tellingly, official race rules meant that his effort – alongside a pool of 48 official competitors – could not be formally recorded. His presence is recorded now though: he is remembered by the titanium “Robert Mtshali” medal which is awarded to those that finish between nine and 10 hours.

Crucially, Mtshali’s efforts would go on to inspire a wave of athletes, including Vincent Rakabele, who was the first Black runner to officially win a medal at the Comrades Golden Jubilee in 1975, and Sam Tshabalala, the first Black winner of the race, in 1989.

Agitation for women’s participation also began considerably earlier than one would think. Frances Hayward became the first woman to complete the race in 1923. Notably, Hayward was refused official participation so she resorted to running the race unofficially. Testament to the thinking of the time, fellow runners and spectators presented Hayward with a silver tea service and a rose bowl.

Nonetheless, like Mtshali, she would go on to inspire generations of women runners, including Elizabeth Cavanaugh, the first woman to officially win the marathon in 1975 and Olive Anthony, the first Black woman to finish the race in 1980.

Since the efforts of Mtshali and Hayward, the marathon, its constituents, and its meaning has been fundamentally transformed, in tandem with the shifts in the wider political dynamic of South Africa.

For one, following the removal of racial and gender barriers, the Comrades Marathon became a staging post for activism against apartheid which was still unfolding in wider South African society at the time. Most famously, record marathon winner Bruce Fordyce – who has notched the gold medal a total of nine times – competed with a black arm band in protest to the marathon’s continued association with the apartheid government. Fordyce, who was joined in his protest action by other white competitors, became a symbol of white runners and athletes using their platform to take a stand against apartheid. Unsurprisingly, he remains somewhat of a cult hero in the Black running community.

Today, the marathon is an altogether different beast. In the 2018 edition, the majority of surnames were Dlamini and Ndlovu – common Zulu surnames – reflecting the marked change in the racial demographics of participants. Furthermore, roughly one third of participants were women and more than 50 countries were represented.

Further highlighting the degree of diversification is the profile of winners. One of the two most decorated Black male competitors is a Zimbabwean, Stephen Muzhingi, who is tied with South African, Bongumusa Mthembu, with three wins. Meanwhile, the most decorated female competitor is a Russian, Elena Nurgalieva, with eight wins to her name.

Significantly, organisers have also reformulated what they consider to be the spirit of the marathon. From the classic “chivalrous” values put forward by Clapham in the 1920s, the spirit of the marathon is now said to be embodied by the attributes of camaraderie, selflessness, dedication, perseverance, and ubuntu - a zulu phrase most commonly translated as “I am because we are.” These are all attributes that are far more inline with post-apartheid South Africa.

This is echoed by the perceptions of our four competitors. When asked what the marathon means to them, Olwethu, who completed his first Comrades in 2018, argued that the marathon was a celebration of South Africans’ perseverance in the face of adversity, their will to overcome, and their embrace of diversity. Olwethu also underscored the role that running has played as a vehicle for health in South Africa.

For David, a white man, it was a symbol that South Africa “has made progress in overcoming a challenging history, but a lot of work still needs to be done.” Both conspicuous and subtle racism persists, societal divisions remain, and there are still numerous barriers to participation, including the lack of resources.

Similar reservations were expressed by Nontobeko and Kayla, who also underscored the issue of safety in South Africa, which prohibits women from freely running, especially those in low-income communities of color. Nontobeko also pointed out that parity is also yet to be achieved in the race as men still account for a sizable majority of competitors. Although she did laud the growing exposure of Black women to running facilitated by Comrades, other competitions, and the boom in the popularity of crew running, which according to her was a net positive for women.

These sentiments underscore a crucial point: while the comrades marathon itself has notably transformed since its initial inception, it has not escaped the realities of the society in which the marathon exists.

More than 25 years since apartheid officially came to an end, racial and gender disparities are still rife – South Africa has among the highest levels of economic inequality in the world, which is dispersed along racial and gender lines. South Africa also has one of the highest incidents of gender-based violence, with women of color in low-income communities being the primary victims. Accordingly, people of color, and especially women of color, are still disadvantaged from birth from partaking in running and other sporting endeavours.

Fortunately, those seeking change can take heart from the evolution of the marathon itself and to use the marathon – and running – as a mechanism for change.

With millions of viewers tuning in from around the world, the marathon serves as an opportune platform for participants to raise awareness to various social issues. Furthermore, running initiatives by Comrades participants can also play a key role in stoking interest among disadvantaged communities, connecting sponsors to those in need and creating a safe space for women to participate in running.

Indeed, just as the values of camaraderie, selflessness, dedication, perseverance, and ubuntu are pivotal to the 25,000 lined up in Durban or Pietermaritzburg for each annual edition of the Comrades Marathon, they are just as pivotal to a South African society that continues its trudge towards a non-racial and non-sexist society. Runners, in their capacity as athletes, members of society and advocates for change, are pivotal to ensure that South Africa crosses this proverbial finish line, with great haste.