Nordic

Exertion

Pioneers of middle-distance running and their battle with amateurism

Words by Emmie Collinge and Phil Gale

Long before East Africa came to dominate middle and long-distance track events and road races, there were the Finns and the Swedes. These two Northern European nations set the pace, leading the world from the turn of the 20th century until the close of World War II. The Nordic domination of that half century is now part of the folklore of running, but it’s worth remembering that there’s more to the myth than Gunder Haag.

It’s hard to pin down a definitive start and finish, let alone highlight the roots and causes of these two parallel stories of success. Dozens of reasons are bandied about as to why these large but largely empty nations achieved so much — what was it about these lean and hardy citizens of the frozen north that propelled them to consistently better the world’s elite, rewriting the record books with alarming regularity?

A little over 100 years ago, athletics was in its infancy. The federations were a loose band of gentlemen and many nations had their own interpretations of the handful of rules that existed. By the Stockholm Olympics of 1912, a sense of order was starting to prevail with the Swedes at the helm; citing rules, noting records and defining ‘amateurism:’ a principle that was at the core of the sport. Around the same time, three brothers from rural Finland, then a Russian Duchy, were setting out on a path devoted to athletics, one which would end up ‘running their country onto the map’ and launching the generation of ‘Flying Finns,’ who would go on to win 10 of the 16 gold medals at the 5,000m and 10,000m at the Olympics from 1912 to 1952. For Finland, the early successes of these men gave the soon-to-be-independent country of three million a new passion. A passion that lays in circles around a 400m cinder track and the same one as the world over.

Pioneers of sorts, the Kolehmainen brothers, Tatu (1885), Viljami (1887) and Hannes (1889), understood that their futures could be changed through success on the running track. As an accessible and affordable sport, running held mass appeal for a country such as Finland, whose economy was largely based on the back-breaking physical labor of agriculture and timber. The common outdoor lifestyle and the necessity to cross great distances on foot or skis, be it to school or work, lent the Finns a natural endurance– an advantage which the brothers seized, seeing every opportunity as a training session and fervently devouring the little international literature that existed on athletics.

They were brought up - as all Finns were at the time – on a diet of hunting, skiing and physical labor, which instilled a fundamental aptitude for hard work and endurance. For Finns, it wasn’t unusual to go out to work as youngsters and all three of the brothers worked as loggers. With the father’s role as breadwinner vital in such a poor country, the loss of their father when Hannes was just six years old further strengthened their work ethic. Left with no choice, they took on more responsibility as the men of the house.

When not working, the brothers devised rigorous training plans, studied running techniques and followed strict diets. Adding previously unconsidered factors like intervals, progression and periodization into their training, picked up by Viljami’s proficient English, they reaped the benefits from their hard efforts and became increasingly revered on the national scene.

At just 17 years old and following in the steps of his brothers, Hannes turned his hand to marathon running. The 1907 national championships, likely Hannes’s first major public outing, saw the 22-year-old Tatu finish 2nd and Hannes take 3rd, two minutes down on his eldest brother, clocking a time of 3:06.17. Despite his best efforts in the subsequent two years, his marathon times hovered around the 3-hour mark and he duly stepped down towards shorter distances—a decision that led to his entry in the history books. With the 1910 departure of Viljami to seek his fortune in America in the professional ranks — where he would run a world pro track marathon record of 2:29.39 in New Jersey in 1912 — the brothers were kept supplied with the latest training philosophies from the States, nurturing their motivation.

As the 1912 Olympics took place (with Viljami now exempt from competing due to his non-amateur status), Tatu and Hannes took the night boat to Stockholm to represent Finland, which was still under Russian control. The Kolehmainen’s rigorous training was clearly paying off, as Hannes won gold in the 5,000m, 10,000m and cross-country race, while taking home a silver in the cross-country team standings. This particular 5,000m still remains one of the most talked-about events in Olympic history, seeing a hotly contested battle between Hannes and France’s Jean Bouin split by just a hundredth of a second on the line. Both athletes were momentous in recording the first ever sub-15 minute 5,000m and taking 24 seconds off the then world record with Hannes’ time of 14:36.6 becoming the new benchmark. But his Olympics weren’t over there: he set an Olympic record for the 10,000m, winning both his heat and final in blistering temperatures. Having won the other heat, Tatu, the eldest brother, surrendered to the searing temperatures that saw only five of the 11 starters finish the final.

Now undisputedly national heroes as brothers, many mourn the fact that Hannes was not allowed to display the Finnish flag during his moments of triumph. Even today, many Finns declare fondly how Hannes decisively ‘ran Finland onto the world map,’ and himself into the list of all-time greats. For the fans back home, his exploits were poured over in the newspapers and one young athlete paid particular attention, a certain 15-year-old Paavo Nurmi, who would go on to echo — and some say better — Hannes’s achievements. Taking his cues from the Kolehmainen brothers’ appetite for training theory, Nurmi dived headfirst into stats and strategy to maximize his performances.

While declared independent in 1917, Finland remained heavily reliant on the hard work of its population to propel its economy. Much like the Kolehmainens, Nurmi’s father died when he was reaching adolescence and left him to provide for the family. Athletics was taking Finland by storm and Nurmi began training four times a week as a 10 year old. His potential immediately became apparent; one year later he raced top-level adults over 1,500m, clocking 5:43, which even today can be considered an impressive performance for a child of his age.

Having set himself the goal of matching Hannes, Nurmi’s steely determination was central to the development of this young, scrawny runner. He focused methodically on bettering his performances and looked to Alfred Shrubb’s expertise for guidance. The efforts earned Nurmi selection for the 1920 Antwerp Olympics where a 32-year-old Hannes, having returned from professional racing in America, won the marathon in 2:32.35. Nurmi took home victories in the 10,000m and cross-country but only finished second in the 5,000m. He was undeterred, concluding that his downfall was his inability to keep the correct pace.

As is widely reported, his attention turned towards time-keeping, with him reputedly never running after those games without a stopwatch in his hand to check his splits. “When you race against time, you don’t have to sprint. Others can’t hold the pace if it is steady and hard all through to the tape,” he explained. This calculated and mechanical approach to racing, mixed with his reserved manner, gained Nurmi the reputation as a runner who had little, if any, fear of his fellow competitors; he went on to compulsively break record after world record. After setting the 10,000m WR in Stockholm in 1921 with a time of 30:40.2, he went on to run new record times in the 1,500m right through to 20km, a distance spectrum that renders him irrefutably one of the all-time greats.

During this period, success on the Olympic track meant virtually an instant invitation to compete on American soil against their current crop of athletes; an opportunity that many seized. Following the Stockholm Olympics, Hannes had joined his brother Viljami for several years stateside, who was making a successful living as a professional marathon runner. As so many Finns had emigrated, Viljami was central to this ex-pat Finnish running community that also included the gaunt, strong-featured Ville Ritola, whose expression always betrayed the effort he put in on the track.

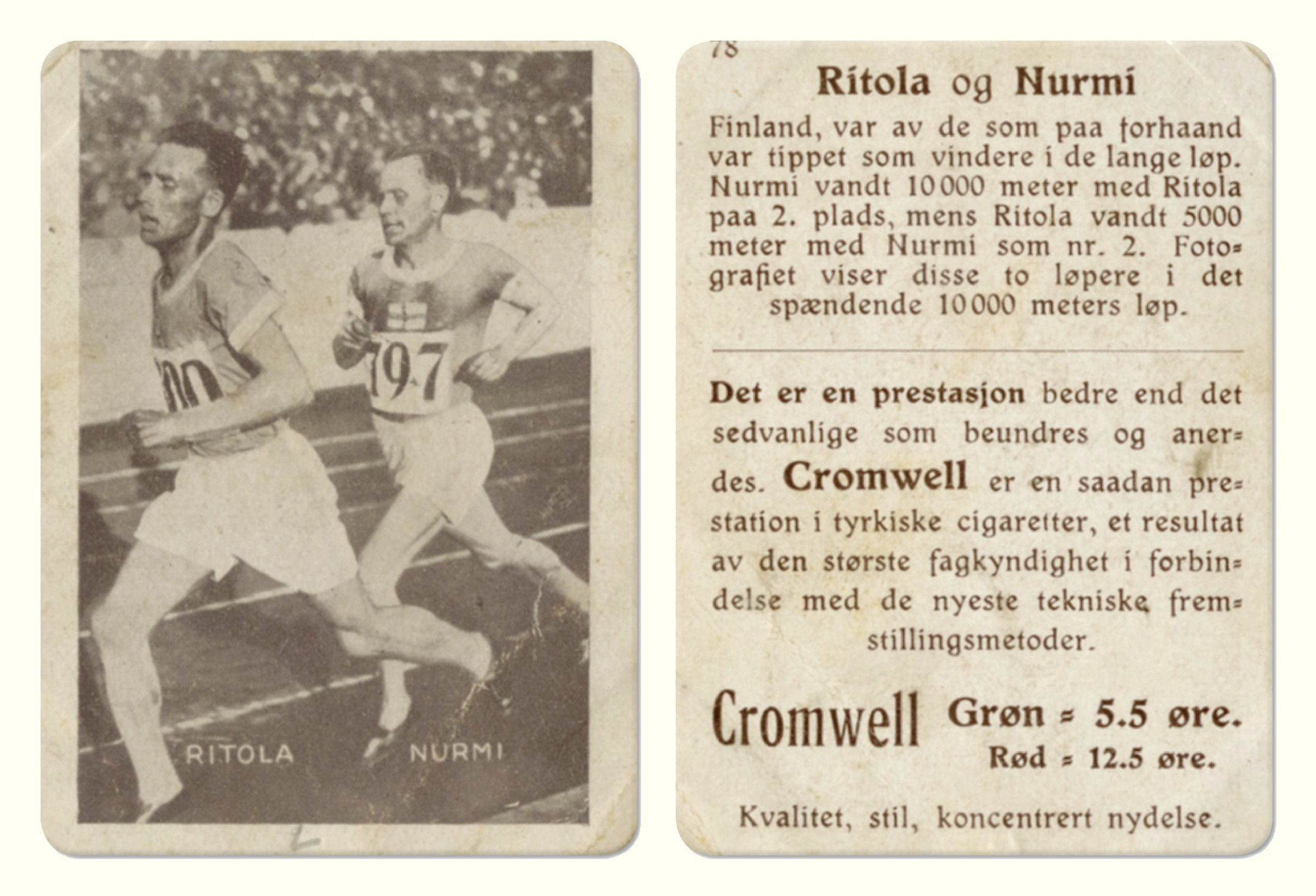

Ritola is argued by many to be the fourth member of ‘Team Kolehmainen’, as he was under the wing of the brothers. A latecomer to athletics, it was not until the 1924 Paris Olympics that this 28-year-old made his debut on the world stage, after repeatedly being urged by the Kolehmainen brothers to race sooner. During these games Ritola shattered the 10,000m world record and took a decisive victory in the 3,000m steeplechase. Walking away with a haul of 4 gold medals and 2 silver medals, the blond Ritola ran his way into the notion of the Flying Finns.

Back at home, the awestruck population of Finland sat huddled around the radio to follow the progress of their now world famous runners, tracking the 32-year-old Kolehmainen’s progress in the marathon, and Ritola and Nurmi’s feats on the track. With the pressure on after Antwerp, Nurmi did not disappoint here, and Paris was perhaps his finest games, seizing victory in the cross-country as well as both the 1,500m and 5,000m events, held just hours apart.

With America now fully ensconced in the romanticism of the Flying Finns too, their presence at track meets and road races was in high demand. In 1925, Nurmi raced 55 times in a 5-month period stateside, winning all but two and earning himself the divisive reputation of having ‘the lowest pulse rate and the highest asking price.’ With negotiable starting fees, the allure of turning professional was strong yet engaging in a sport where financial gratification would long be a contentious issue.

Fortunately for them, the amateurism rules remained laxly policed, so both Ritola and Nurmi went on to compete at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, facing each other in many of the same events. It was not until 1932 with Nurmi’s sights firmly set on defending his 10,000m gold and the marathon, that the IAAF took the decisive step to suspend him prior to the games for accusations of professionalism.

From its creation in 1912, the IAAF [christened the International Amateur Athletics Federation] had long retained a blinkered, idealistic view towards amateurism, which they clung to until a new, more realistic definition was drafted in 1982. Throughout the century, many athletes succumbed to the draw of high dollar races, enticed by the satisfaction of receiving compensation for their exertions and not averse to returning to their homelands as wealthier citizens.

Yet it was a widespread issue that didn’t just affect the Flying Finns. Sweden had long played second fiddle to the successes of their Finnish neighbour. But with their state-supported push for health and fitness and their habitual outdoor, hardy lifestyles, they were poised to give birth to a generation of world dominating middle-distance runners, ripe to take the mantle from the Flying Finns.

Today the two most well-known Swedish milers of the 1940s are remembered warmly with a wry smile and a shrug, although a slight sense of disappointment prevails; disappointment that their peak performances took place during WWII when no major championships were held, and disappointment that they too, were handed lifetime bans. Gunder Hägg and Arne Andersson drew in large audiences in their home country and the world’s gaze was fixed on the two lean athletes who broke record after record, providing a welcome distraction to the devastating hardships that WWII brought with it.

After an 80-day period in 1942 in which Gunder Hägg broke 10 world middle-distance records, Sweden didn’t hesitate for a moment before crowning him sportsperson of the year. Hägg’s antics on the cinder tracks of Europe and America provided escapism, and his charming nature rendered him a pawn in the world of politics. Yet born in 1918, Gunder Hägg was by no means unique with his talent for running. Much like Finland, Sweden too had a thriving local athletics scene and subsequent talent pool that led to a period of Swedish dominance, with its roots coinciding roughly with Henry Jonsson’s 5,000m bronze medal at the 1936 Olympics. Often overlooked today, Henry Jonsson, who later went by the name of Henry Kälarne, was from the same region as Hägg and held the world records for 2,000m and 3,000m before the more famous athlete clinched them.

Not unsurprisingly for a Nordic country, both Jonsson and Hägg had grown up on a diet of farm and forestry work with the need to cover long distances on foot or skis. With such fundamental endurance already shaping their physical capacity, the Swedes soon became renowned for their running prowess and the world happily clung on to their successes at a time when the war was doing its utmost to infringe on daily lives.

Best known for his light and fluid running style, Hägg’s record-breaking times and endearing personality rendered him hugely popular with audiences around the world. His achievements, while seemingly done with ease, were the result of a meticulous training schedule and an awareness to work throughout the year, rather than just the season. Opting to base himself for periods in central Sweden’s Vålådalen, it was commonplace for Hägg to run his interval sessions on winter’s frozen snow and summer’s swamp-like ground. His training was methodical and consistent, incorporating much off-road running and hill work; he openly preferred to train in nature where the views could keep him motivated.

As hard work morphed into victories, he duly received standard invitations to compete in Europe and America, leaving his home population glued to radio stations to follow his progress. As the war raged, his track feats were touted and he was arguably a fine distraction for the nation. In 1943, the tall, athletic-looking Swede was greeted by the Swedish king and government as he clambered down from the airplane, weary after a packed four-and-a-half month tour of the USA, where he’d gone unbeaten in every race and decisively dominated against America’s then star, a certain Gregory Rice, who himself had a 65-race string of victories behind him.

On the national scene, Hägg’s fiercest competitor was Arne Andersson, with whom he faced many often-recounted battles and they historically lowered the world’s best times repeatedly through the earlier part of the 1940s. Yet despite beating Hägg’s world 1,500m and mile records while Hägg was on his 1943 tour of the USA, Andersson never quite reached the same level of fame, leading Swedes today to conclude that as an academic, he perhaps didn’t live up to the romantic and altruistic idea of the strong man from the woods. But both runners had different styles and it was the pace-setting, pack-leading style of Hägg that won favour with the Swedes, over the late-kick habit of Andersson.

This rivalry led to two key races between Hägg and Andersson, cementing their place in running history: one in 1943, which saw a capacity crowd at Mälmo stadium, urge both runners on to a new world record for the mile, a race that was ultimately won by Andersson in a time of 4:02.6; and the other in 1945, which saw Hägg race to reclaim the record in 4:01:4. Hägg’s new world record stood unbeaten for a further 9 years until Roger Bannister’s epic breaking of the 4-minute barrier.

National pride aside, the focus on these two Swedish greats weakened at the end of the war. During the conflict, the IAAF and Swedish federation had turned a blind eye to the discrete sums of money these runners received from race directors. Then In 1946 they decided to act, handing a lifetime ban to Andersson, Jonsson and Hägg amongst others. Now exempt from future competition and bemoaning the lack of international events during WWII, these greats lacked the opportunity to toe the line at major competitions. But this should not detract from their achievements, they represented an era of Nordic dominance for middle distance running on a par with the Flying Finns. During the 1940s, there were 25 instances when Swedish runners broke individual world records and the Swedish middle distance relay teams set new world records on 8 occasions over 4 x 800m, 4 x 1500m and 4 x 1 mile, which surely gives them equal rights in the claim of Nordic dominance.

Amateurism may have suffered, with many asserting ‘shamateurism,’ but for both Finland and Sweden, the string of great middle distance runners was born out of a culture of hard work with the act of running doubling as an outlet for their stringent work ethic and aptitude for physical exertion. Led by their internal drive, the support of fans worldwide and the demands of the media, more records fell and they gained huge medal hoards. But this success came through sacrifice, from hours spent outside of already fatiguing work hours to push their bodies.

As the majority had to go unpaid for time missed from work due to the demands of competitions, it was only a matter of time before these world-leading athletes would look to financial compensation for their efforts. Some might call it the end of the ‘true’ era of amateurism because of the arrival of paid sport via the side door, whilst others could argue that it was the precursor to the modern Olympic era. Whatever your standpoint, it is impossible to not regard these athletes as role models and pioneers, who shaped the future of middle-distance running, carving out training techniques and pushing the boundaries of what was considered possible.