THE FELLS

Northern England can be a bleak and desolate place, all windswept moorland and steep-sided post-industrial valleys. It’s a landscape that has inspired an athletic tradition all of its own: fell running.

Photos by Harry Engels

Words by Andy Waterman

There’s more crossover now than there used to be be” says Ron Hill, the 1970 Boston Marathon champion amid the post race hubub that has descended upon Barley Village Hall. “Twenty years ago, if you ran on the road you were a road runner, and the fell runners tended to stick to the fells. You get a lot more road runners trying the fells than you used to. Personally I think one benefits the other. I didn’t do a lot of fell races — I did a few — but I ran on the fells a lot, and I found it built the strength up, so in an out and out fast road race the strength was there. You had to do the speedwork too, but running in the fells built the strength.”

I know what he means. I’ve just raced over nine miles, and thanks to the elevation — 1800ft — and the boggy terrain, I feel about as exhausted as I’ve ever felt after a 1hr 20min run. I say run, but there was a fair amount of walking in there too when the gradient got really steep. My legs feel at once empty and full of lactic, like I’ve been riding a bike that’s stuck in its hardest gear. If anything is going to build the strength needed to become a champion in any element of endurance running, fell running is surely a good starting point.

To the uninitiated, fell running is a lot like trail running, only without the trails. It’s a sport native to the rugged north west corner of England, although it strays further north into Scotland, and west into mountainous Wales. Unlike trail running, fell racing is largely a free for all — if you want to take the direct route to the top of the mountain, scrambling up the scree, you’re entirely at liberty to do so. If you think it would be faster to yomp through knee deep grass and peat bog, rather than following the obvious trail around the edge of a moor, that’s your choice. If you think the fastest way to get to the bottom of a steep muddy field is by sliding on your ass, well it’s not dignified but many great champions of the fells have done it before. So long as you make it through the checkpoints in the right order, the route you take is largely up to you. As a result, fell running is very much about fitness, but it’s also about mountain craft, local knowledge and strength — of both character and sinew.

It’s March 7, 2015 and I've ventured to the small village of Barley in Lancashire, to take part in the Stan Bradshaw Pendle Round. The race is held in memory of its namesake Stan Bradshaw, who died in 2010 aged 97. He was a legend of the fells, in 1960 becoming only the second runner to break the 28-year-old record of Bob Graham, who famously ran 66 miles around the English Lake District, taking in 42 of its peaks along the way. To this day, the Bob Graham Round is a rite of passage for any fell runner, and it’s broken more than a few hearts. Only last year, US trail running legend Scotty Jurek attempted the route, arriving at the finish just 16 minutes shy of the cut off needed to gain entry to the Bob Graham 24hr Club. Stan Bradshaw, the man we are running to remember, ran his last round at the age of 65, to mark his arrival at the UK retirement age. “Stan was the club’s most illustrious member — well, apart from Ron Hill, but we don’t mention that” says the race organizer Mike Eddleston of the Clayton-le-Moors Harriers, winking at the grinning Ron Hill. “When Stan died in 2010”, says Eddleston, “we decided we would re-route and rename a race that we always held in March, the Half Tour of Pendle to be the Stan Bradshaw Pendle Round in his memory. It goes nearby his cabin, where he’d brew up and watch the world go by and maybe jog from there and run round the fells.”

March can be a cruel month in the north of England. At one moment Spring teases its arrival, snowdrops pushing through the mud, the sky cast blue and the shadows long; then just as complacency sets in, Winter returns, blasting the fells with snow and frigid, swirling winds.

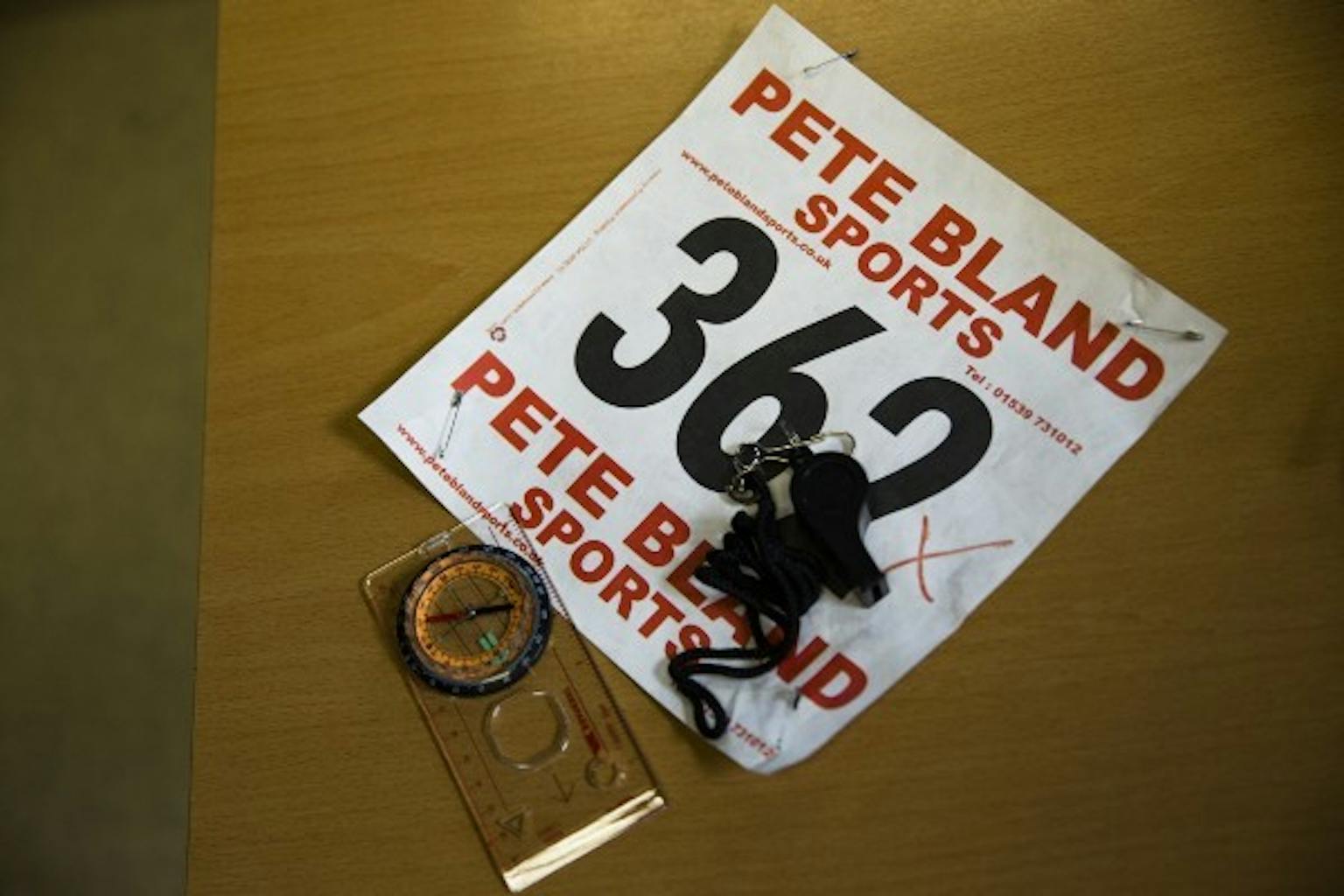

There’s a stoicism among the fell running community that the next band of rain/snow/sleet is only a few hills away — if it isn’t cold and wet at this moment, it soon will be — and it’s this stoicism that surely informs the rule that everyone must carry full kit, consisting a map, compass, whistle, waterproof jacket, gloves and waterproof pants. Amid the sunshine falling on the village of Barley, runners pack waist packs to carry all this gear and pass the organizer’s kit check.

The village is tiny and quaint, the houses built of traditional stone, a small river runs through the middle, underneath a hump back bridge, barely wide enough for two cars to pass each other. Look up and the 1800ft Pendle Hill dominates the skyline, hulking green and brown over the blue-black water of Ogden Reservoir. To many, the hill is most closely associated with the 1612 trial of the Pendle Witches when 12 women were charged with the murder of 10 people by means of witchcraft. One died in jail, one was acquitted, and 10 were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. To this day, every Halloween large numbers climb Pendle Hill in search of the supernatural.

Painfully aware of my lack of local knowledge, I line up at the start somewhere towards the back of a field of some 200 runners to ensure I always have someone to follow. The weather is good, in as much as it’s not raining and there is decent visibility. Eddleston gives the sign and off we go, shuffling up a paved 30 per cent gradient towards the first proper climb. By the time we reach the top of Pendle Hill, we’ve covered two miles in 23 minutes, and climbed 1000ft. I’ve been reduced to walking on a number of occasions, but no one has passed me and I’ve passed plenty. I feel good, and passing the cairn at the summit, with the wind at my back, I reassure myself that we’ve got a long downhill from here.

First mistake.

Richard Askwith published Feet in the Clouds, his lore of fell running, in 2004. A London-based newspaper journalist by profession, he discovered fell running late and dedicated much of his thirties onwards to it, particularly the challenge of completing the Bob Graham Round. Feet in the Clouds is a fantastic evocation of a fell running year, featuring interviews with many of the leading protagonists of fell running’s past and present, as well as exploring the roots of the sport, from professional guides races in the Lake District to the birth of amateurism, to the mixing of the two codes. Askwith’s writing inspired a resurgence in fell running, and to a large degree, inspired Meter’s trip to the north west of England.

One of the take-homes from the book is that the climbs are brutal, and the best way to tackle the descents is by removing your brain at the top. “Brakes off, brain off”, as he puts it. Having recently re-read Feet in the Clouds, I am mentally prepared for both the climb and descent of Pendle Hill; what I haven’t counted on is the endless slog across faintly descending boggy moorland. Every four of five steps there is deep peat trench that needs to be leapt over; the steps in between are on sopping wet grass, no rebound, no speed. This is where the strength comes in and the real fell runners start to pass me. They glide over the ground intuitively finding traction where I find only the slick and soft.

When I see one of these runners switch left off the obvious trail and into the dense, matted grass, I follow, reasoning that only a fool or a local would take such a route, and as I’m now further towards the sharp end of the race, this guy is most likely no fool. If the trail sapped strength, this is even worse — every step needs to be approached with perfect technique to get your lead leg up and over the softness underfoot. We arrive at the bottom of the descent barely having noticed any increase in speed whatsoever.

What follows are two more hills, passing Stan Bradshaw’s hut in the low point between the two, and then a brutally steep descent back into the valley we started in. Finally, my mental preparation comes into play and I bound down the hill, passing three or four runners in under half a mile, and only coming close to disaster on half a dozen occasions. The last climb is a cruel retracing of our steps an hour earlier, but nowhere near as cruel as the final run in to the finish, which on paper is flat-to-downhill, but in reality is a heartbreaking slog through sheep shit and knee deep mud, that ensures we cross the line on the verge of complete physical collapse. I complete the race a few seconds under 1:20 claiming 20th spot, 9 minutes behind the winner. I’m happy with that, and feel inspired to explore this world more. Luckily, with the Feet in the Clouds inspired renaissance still going strong, there are races every weekend, often two or more on one day.

“We’ve been blessed with some great weather today”, says Eddleston when I speak to him after the race. “The worst we’ve had is almost a white out, and you have to consider pulling the race. We’ve never done it so far, but we have run it in driving rain and fog where you can’t see anything, and navigation and local knowledge really comes to the fore.”

We’re walking back towards the finish area — a farmer’s field that would normally be home to a herd of sheep — when an elderly man in the fell runner’s uniform of short shorts and club singlet walks towards us.

“Have you shortened the course?” he asks, jokingly, explaining he’s twenty minutes faster than last year.

“No, you’re fitter than ever”, says Eddleston, laughing.

Fell running is a true grassroots, community-centred sport. Entry for the race cost £5 and had to be paid in advance by check — no one is making a quick buck from this pursuit, everyone is here for the love, including the poor souls who have given up their Saturdays to man the checkpoints out on the tops of the moor. While we ran past their windswept outposts, keeping warm through exertion, they were stood there for three hours with nothing but a thermos of hot tea to keep the chill at bay. Is it easy to organize an event like this?

“There’s a good core of volunteers in the club,” says Eddleston, “and when push comes to shove, you get the marshalling. It isn’t always easy, but once they volunteer, they know what they’re signing up for, they never back out whatever the conditions.”

Fell running breeds that kind of hardiness and Feet in the Clouds is full of tales of people running till the skin on their feet falls off, or running through the most miserable of circumstances until they come out the other side as a local legend.

And yet for all the talk of hardness, fell running ranks among the most friendly of running disciplines; how many races have you been to where former Boston champions rub shoulders with average Joes, sharing a joke with them after the race over a mug of hot soup in a modest community hall? The real magic of amateurism is alive and kicking in the hills and valleys of the British fell running scene, long may its renaissance continue.