Malcolm Gladwell (MG): So the Speed City Project, where did that come from?

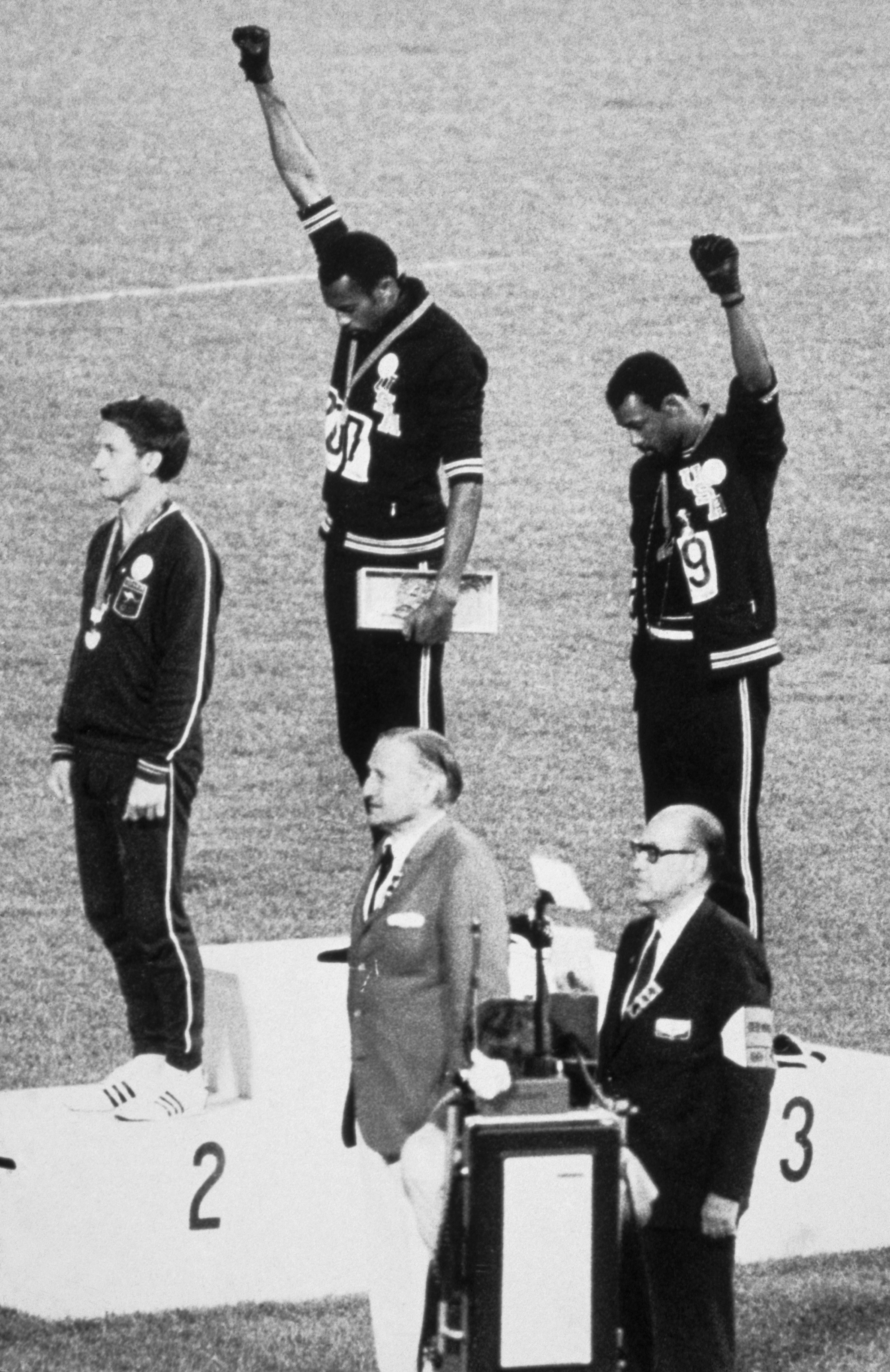

Matt Taylor (MT): It's something that's always intrigued me. The image of Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium in Mexico City with their gloved fists raised in the air – it has to be one of the most recognizable photos of our generation. But a photo only captures a moment in time, right? I always wanted to know more: how did that moment come to be? Who else was involved? What happened afterwards?

As I got to learn more about that story, there were really two parts that felt compelling to me. One was, how did this tiny school in California produce so many world class athletes? San Jose State was not an athletics powerhouse, but in the 1968 Olympics, they won three gold medals and a bronze, which was amazing. And then two, the legacy of Speed City, its impact on the world as we see it today, both in terms of athletic performance, but also social justice.

You can make the argument that without Speed City, there might not be a Usain Bolt, and without Speed City, there might not be a Colin Kaepernick because in both of those cases, there's a direct link specifically from Bud Winter, the coach, and Dr. Harry Edwards, who was an athlete on the track and field team.

MG: It's amazing. I remember as a kid seeing [that photograph] for the first time. Every part of this story is so wild and unexpected, and the idea that everyone is from the same little tiny school in San Jose. I didn't even know there was a San Jose State! Talk a little bit about Bud Winter and his coaching ideas. There's something astonishingly contemporary about him, right?

MG: What's the Usain Bolt connection? Is it that Usain's coach is a Bud Winter disciple?

MT: The link between Bud Winter and Jamaica's sprint dominance is really interesting. Dennis Johnson was a Jamaican athlete that went to San Jose State for college, and he himself was an incredible runner, he tied the world record for the 100 yard dash multiple times. So Dennis Johnson trains directly under Bud Winter for four years of college, and then after graduation, he goes back to Jamaica to develop a U.S. style college athletics program because that didn't exist on the island. At the core of that program was Bud Winter's relax and win training philosophy.

The connection to Usain Bolt is that, in 1966, Dennis Johson invites his former coach, Bud Winter, to come to Jamaica for a series of sprint seminars, and one of the attendees at those seminars was the young Glen Mills. And Glen Mills, in 2004 or 2005, becomes Usain Bolt's coach. Usain Bolt at the time was injury plagued and somewhat underachieving based on his potential, and Glen Mills was able to transform him from that athlete to what we know today as the world's fastest man.

MG: It's so funny because the picture you have of Usain Bolt in your head is the perfect embodiment of Bud Winter's ideas. He's gliding down the homestretch kind of untroubled and unruffled, and yet, he's going faster than any person ever in the 100 or 200m. It's that paradox – he doesn't look like he's running hard.

MT: No, and so relaxed that he actually has time to celebrate before he crosses the finish line because everyone else behind him is grimacing, and he's smiling.

MG: I'm reminded of the semi-final at the world championship: Usain Bolt is running next to the Canadian Andre DeGrasse (who is again a perfect Bud Winter athlete), and the two of them start chatting. They're so perfectly relaxed and in command that they turn to each other. I don't know what they said, but they're laughing about something. It was a lovely moment. The other seminal figure in Speed City is Harry Edwards, and just the idea that Harry Edwards was a Bud Winter athlete.

MT: Right, another Bud Winter athlete. So he was on the track and field team and he was a discus thrower. He actually butted heads with Bud Winter – one of the only athletes that had some tension with Winter – and he went on to become the leader and an advocate for racial justice leading into the 1968 Olympics.

MG: Yeah.

MT: And there was a moment where the athletes were thinking about boycotting the Olympics, and instead of boycotting, they took a vote and they decided to go. In some ways that decision probably created more positive change than had they boycotted, because that moment of Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium would not have happened. It's 50 years later and it's still a moment that we talk about. So yeah, Harry Edwards was obviously a seminal figure in the 60s, but then he also started the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Fast forward to Colin Kaepernick and he is an advisor for Colin Kaepernick, and so there is just this amazing legacy, both from a sports performance and a social justice perspective that comes out of Speed City.

MG: More than Kaepernick, Harry Edwards has continuously, since the 1960s, been at the center of virtually every argument, controversy, whatever that involves sports and justice and race, right? I mean, there's not been a single public moment around those issues where Harry Edwards wasn't front and center.

MT: That's right – he’s still a very prominent figure.

MG: I came away with just an enormous amount of respect for Harry Edwards. I mean, he really is an incredible innovator and trailblazer, and for 50 years he's been at the front and center of this. I mean, it's just an astonishing reign as the intellectual and emotional leader of the racial justice fight in sports.

It's odd how we forget how silent athletes were up until that point – that it was felt that part of the definition of an athlete was that you were above politics. By virtue of being an athlete, it never occurred to anyone that you would have standing in any other domain, and Edwards comes along and says, "No, no, no, the kind of stature that you gain from athletic prowess allows you to speak out on other issues of importance in society.” The difficulty that the NFL had in dealing with Colin Kaepernick shows that even today, 50 years later, people are still wrestling with that idea.

MT: Yeah, they do. I mean, it's the “shut up and play” thing. But the thing is, sports are a global platform unlike any other. I mean, sport transcends geography, race, religion, so it gives these athletes an incredible platform to speak out on issues. And we've seen over time that sports and athletes have used that opportunity, and Tommie Smith and John Carlos were two of the first. They weren't the first, but they definitely were at the beginning. And the reason that that moment became so iconic is because 1968, I think, was the first year the Olympic games were broadcast live in the U.S. in color on television. The documentary, The Stand, does a really good job of illustrating how it all unfolded.

MG: Tell me a little bit about the Tracksmith Foundation. What are you trying to do with that? That's sort of a reflection of the same interest that you have as a company in social justice issues.

MT: The goal of the Tracksmith Foundation is simple: to give more people the opportunity to participate in track and field. I think the lessons learned from being part of a track and field team are the lessons that help create a more inclusive society, and the way that the foundation began is that we started supporting the efforts of Russell Dinkins, who became an advocate for saving college track and field programs from being cut. Often the track and field program is one of the first to get cut at universities because it's such a large team, and so if you look at it purely from a budget perspective, it's an easy target. But outside of basketball and football, which are revenue-generating sports and have their own mini-economies, track and field provides more opportunities for black student athletes than any other sport. And so when track gets cut, it disproportionately reduces opportunities for black athletes. And so Russell, who is the foundation's Executive Director, has been at the forefront of saving these programs.

The link here to Speed City is interesting too, because San Jose cut its track program in 1988, because of budget cuts and Title IX and a few other reasons, but then reinstated the program in 2018, before some of these more public cuts happened. They reinstated the program purely for the reason of the history and the importance of the team going back to Bud Winter and Tommie Smith and John Carlos and Lee Evans and the others.

For more on this story, you can listen to the first episodes of Legacy of Speed on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. The Stand is available to stream via Amazon. Stay tuned for more from Tracksmith and Puma on Speed City this summer.