When It Hurts, Go Faster

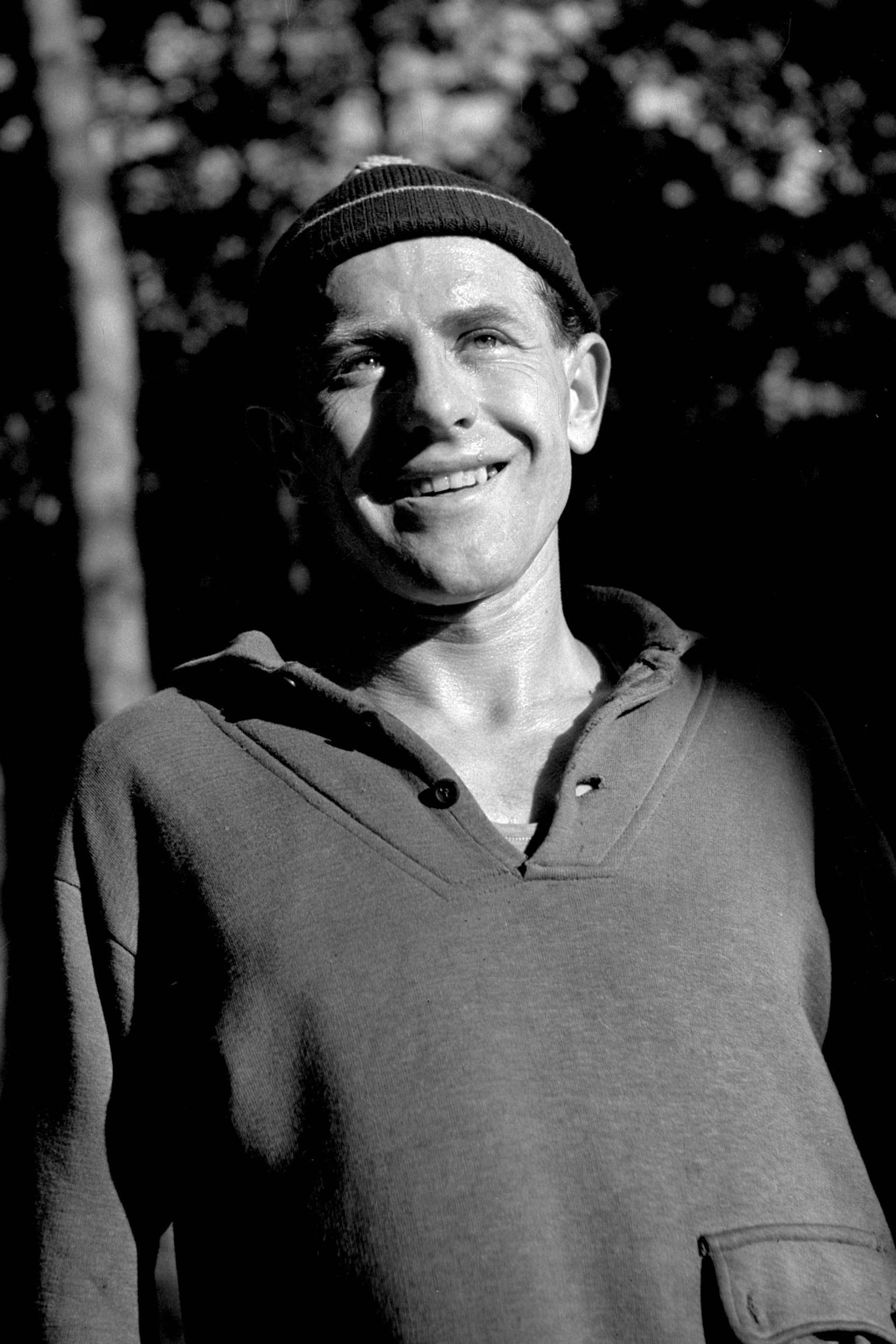

Locomotive. Beast. Frankenstein. Fool. Genius.

Read enough biographies and articles about Emil Zátopek and you’ll be struck by the language used to describe the legendary athlete - the only person to win the 5k, 10k and marathon in the same Olympics (Helsinki 1952). You’ll likely be struck by his own words as well. He was loquacious and sage. Known for talking during races (like “Today we die a little,” supposedly uttered at the starting line of the 1956 Olympic marathon in Melbourne), his biographies are littered with bon mots and inspiring quotes.

Born September 19, 1922 in what was then Czechoslovakia to a working class family with eight children, Zátopek’s early life likely forged the grit and tenacity that marked him as an athlete. At barely 15, he left his family to work in a factory. It was there that he got his start in running. Forced to enter a company-wide race, he surprised himself by coming second. From that day on, he was possessed. Determined to see just how fast he could go, he demonstrated an insatiable commitment to training and a curiosity for experimenting with the work.

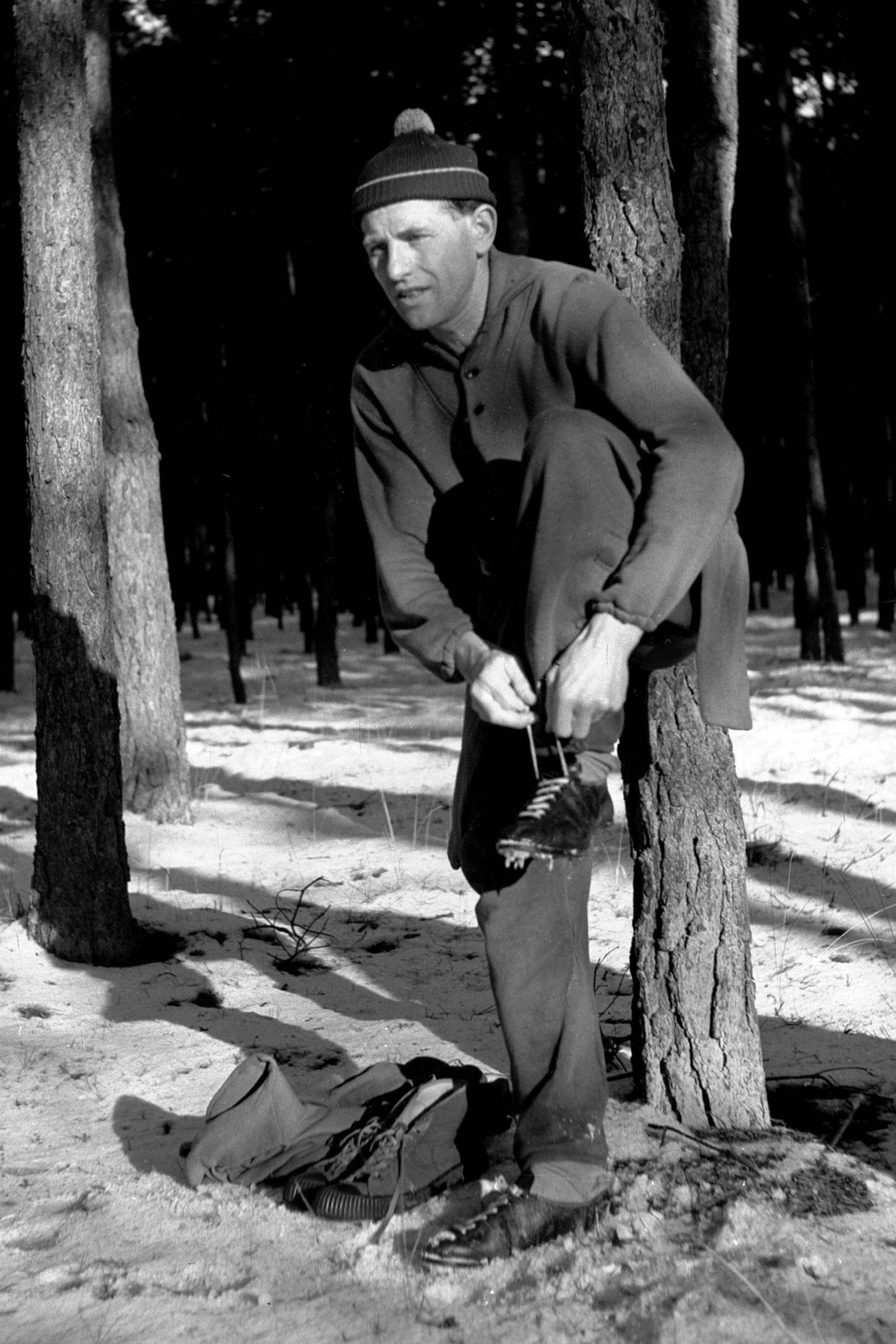

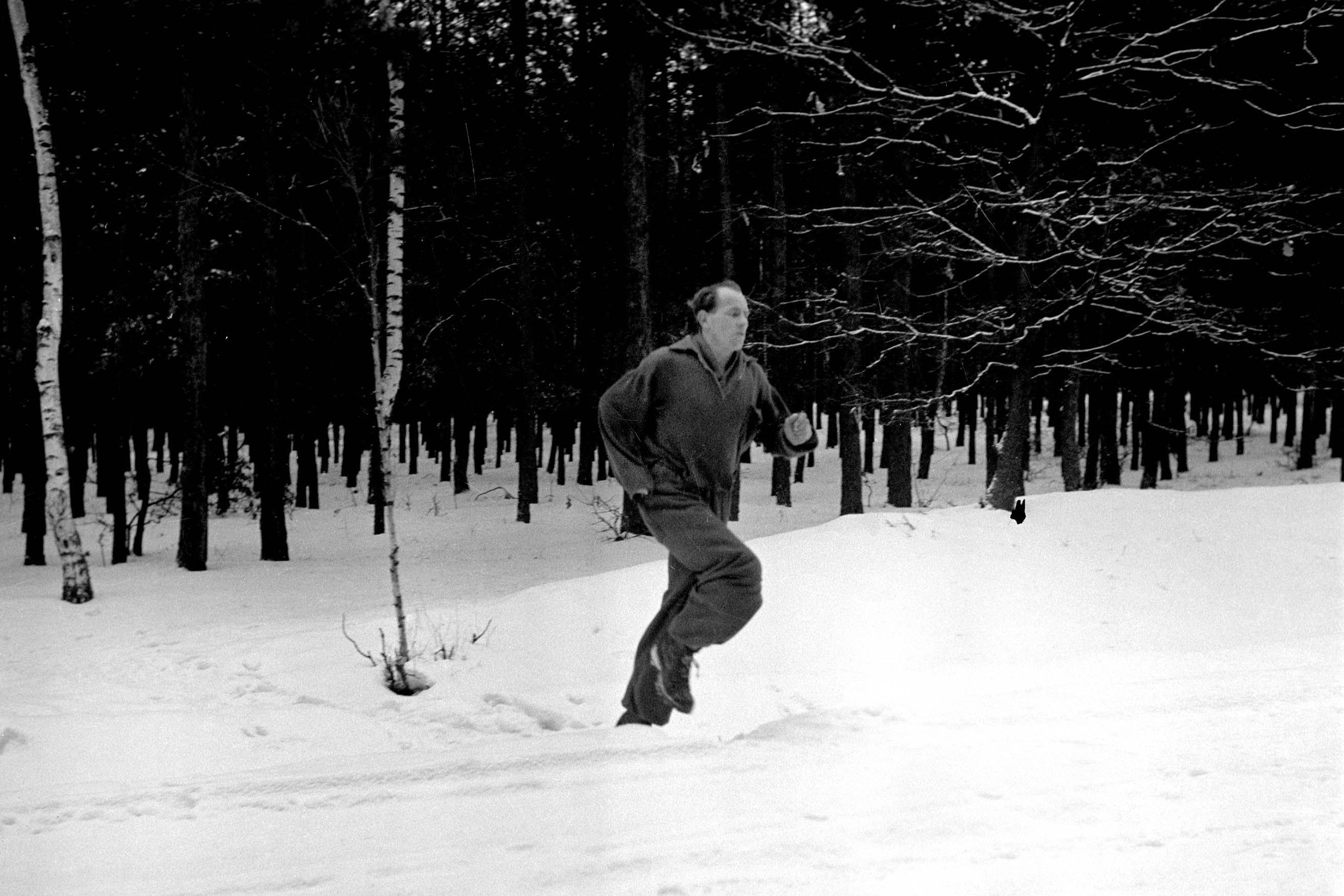

Indeed, Zátopek’s training regimen has become the stuff of legends. These Johnny Appleseed-style tales have become so entrenched in running lore that it can be hard to separate fact from fiction. No, he didn’t carry his wife on his back during workouts, but he did regularly train in army boots. In the snow. And at night with a torch to light his way. He experimented in hypoventilation, trying to see how far he could hold his breath between trees in the forest without passing out. Forced inside to do chores, he jogged in a tub of soaking laundry. He spurned stopwatches and ran largely by feel.

Written in a list, these stories read more eccentric than innovative. And yet, themes emerge. Zátopek was voracious, curious and rigorous in his training. He understood that racing doesn’t happen in a vacuum and therefore training shouldn’t either.“There is a great advantage in training under unfavourable conditions,” he noted. “It is better to train under bad conditions, for the difference is then a tremendous relief in a race.”

This racing mindset informed his commitment to interval training. Zátopek believed in running fast to race fast. One of his most remarked upon training periods included five consecutive days of 40x400 with a 200 meter jog in the morning followed by 40x400 again in the afternoon. He explained his rationale as such:

“When I was young, I was too slow. I thought I must learn to run fast by practicing to run fast, so I ran 100 meters fast 20 times. Then I came back, slow,slow,slow. People said, ‘Emil, you are crazy. You are training like a sprinter' and 'Why should I practice running slow? I already know how to run slow. I want to learn to run fast. Everyone said, ‘Emil, you are a fool!’ But when I first won the European Championship, they said: ‘Emil, you are a genius!''

It’s interesting to contrast this training to that of Eliud Kipchoge, the Zátopek of the modern era in both zen-like quotability and performance. Per Scott Cacciola of the New York Times, Kipchoge “estimates that he seldom pushes himself past 80 percent — 90 percent, tops — of his maximum effort when he circles the track for interval sessions, or when he embarks on 25-mile jogs. Instead, he reserves the best of himself, all 100 percent of Kipchoge, for race day.”

Of course, it’s no surprise to read of the differences in training styles between Kipchoge and Zátopek. Sixty-years of sports science will do that. The reality is that Zátopek’s intensity was likely counterproductive up to a certain point. Two months before his incredible 1952 gold-medal trifecta, doctors told him not to compete due to an infected gland. Before the 1956 Olympics, he developed a hernia, which required surgery and almost sidelined him for the Games. He retired not long thereafter.

And yet, Zátopek’s legacy is not in the minutiae of his workouts or the idiosyncratic details of his diet (he occasionally ate birch leaves, channeling his inner bounding deer). Zátopek approached his training with a zeal and novelty to which we should all aspire. He loved the process and found a creative outlet in it.

Interestingly, what Eliud Kipchoge and Emil Zátopek do share, beyond a penchant for world record-breaking and winning streaks, is their philosophical approach to running. Indeed, remove attribution from any number of their quotes and the results are ripe for a game of “who said what?”

“Become comfortable with being uncomfortable. Accept change.”

“Pain is a merciful thing – if it lasts without interruption, it dulls itself.”

“If you don’t rule your mind, your mind will rule you.”

“By a persistent effort of will it is possible to change the whole body. The athlete must always keep in mind this concept of change and progression. He must never accept his limitations as being permanent, because they are not.”

Kipchoge. Zátopek. Kipchoge. Zátopek.

Perhaps it is the marathon itself that inspires such philosophical musings. The Greeks invented it after all. Or perhaps it’s something essential in these men that draws them to the distance. The same masochistic desire to discover what more is possible. To redefine limits.

Or maybe, once again, Zátopek explained it best.

“We are different, in essence, from other men. If you want to win something, run 100 meters. If you want to experience something, run a marathon.”

Words by Lee Glandorf. Photo Credit: Alamy.

Embrace The Unexpected

Our New Merino Shawl Collar, Inspired By A Running Great